The Brickbuilder - December 1912

The Emmet Building, New York City

MADSON AVENUE AND TWENTY-NINTH STREET

J. STEWART BARNEY AND STOCKTON B. COLT, ARCHITECTS

The architects of the Emmet Building were presented with a rather curious problem which arose from the sentimental attachment of the owner to the site. He had lived on Madison avenue for most of his life, and while realizing that the character of the street sentimental attachment of the owner to the site. He had lived on Madison avenue for most of his life, and while realizing that the character of the street had changed from a residential to a business one, and that it was impossible longer to continue the occupancy of the old-fashioned brownstone house, either with comfort or with profit, he did not desire to move from the location. He therefore erected an office and loft building, not as a speculative procedure, but as a permanent investment, and made the upper story of it into a housekeeping apartment. In as much as the building was to be not only an investment but his own permanent residence, he thought it desirable to erect something of good architectural character, which, although it should be a practical loft or office building, should at the same time have the distinction which every one wants in his own private house. The architects,by a somewhat different treatment of the upper story, have made plain the line of demarcation between the business portion of the building and the residence, and have successfully solved a very interesting problem, as will be seen by the accompanying illustrations.

In the design of the building emphasis was laid as strongly as possible on the vertical lines, in a manner not dissimilar to those in the Times Building, the West Street Building and the Woolworth Building, three of the most excellent tall buildings in New York.

The stories intermediate between the base and the large arches at the twelfth story are perhaps the most agreeable that have yet been designed in this type, which although in its vertical treatment is suggestive of Gothic, is far from being derived from Gothic; the base in fact rather resembling the early French Renaissance combination of classic forms.

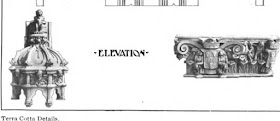

One of the most interesting features in the whole structure are the columns of the lower two stories, which are of green marble inlaid with vertical lines of limestone, — a scheme which in form has perhaps had prototypes in early Gothic, but which in such a combination of material is a unique, beautiful, and clever piece of work. The first three stories are faced with limestone, and those above are of architectural terra cotta with metal panels between the sills of the windows and the heads of the windows below them, through the shaft of the building, with an attic of brick and terra cotta.

The use of the terra cotta in this building requires particular and favorable comment, in that no attempt has been made to disguise the nature of the material, which is frankly a fireproofing for the steel work within. The accuracy with which the vertical lines have been maintained with no feeling whatever of motion adds to the reputation of the material. The terra cotta is of a warm gray limestone color with dark olive green for the background of the band below the third story, in the arches at the twelfth, and in the cornice, but this color has not been made to serve the place of form, but rather to emphasize and decorate form; a method much more satisfactory in the long run than any attempt to replace form by color. We have become accustomed to the construction of elaborate and beautiful detail in the material, but it is interesting to learn that the statues and grotesques are cast terra cotta, a most unusual procedure in such large pieces, and which opens up further fields to its already extensive possibilities. The modeling of these pieces is of an unusual character.

Perhaps the greatest element in the success of the treatment of this building is the fact that the architects have scaled their detail down to that of the material employed, without losing character and distinction to the building as a whole. They have not found it necessary to employ enormous overhanging cornices, which are not only bad as reducing the light on already too narrow streets, but are, of course, when constructed in the usual way merely elaborate shams. They have managed to terminate the shaft firmly and distinctly by multiplying the small members, which even in their multiplicity are neither confused nor involved, but clear and logical both as to their architectural fitness in the design and as to explicit revelation of the material employed. It is refreshing to find this material, which is so useful and satisfactory both in appearance and price, frankly expressed, with an impression of great richness which in any other material would be almost prohibitive. The small pieces in which terra cotta can be properly manufactured, and the plastic quality of the detail as opposed to the large pieces and carved detail of stonework, can be used to quite as good effect as stone for certain positions; and to endeavor to conceal the material as if it were something to be ashamed of, is not the highest form of art. The Greeks very frequently employed terra cotta in decorating their stone architecture; but they did not use it like stone ; and this is one of the many lessons of the classic school we have left unlearned.

The same thoughtfulness in regard to the genuine structure of the building as a steel framework overlaid with a fireproof covering is observed throughout. Every one knows that none of the great marble or granite columns in the lower stories of tall buildings are anything but veneers; here the architects have obtained a firmness of design resulting from an order in the lower story with out attempting to force it to express a structural function; they have simply mosaiced the various members which make up an order, into an agreeable composition used as a decorative motive only. The same thing is true of the shaft, where the terra cotta is treated purely as a fire proof, weather-proof, and decorative covering for a steel frame.

It may be said of this building without lack of appreciation of other tall building work, that it is one of the few structures which approximate the true line of development of tall building architecture, both in its design and in selection and use of material. The classic order is neither neglected as useless nor employed as a fundamental, certain motives of Gothic and Renaissance work have been, if not embodied entire, at least suggestively useful in the design, and the whole building hangs together in a manner which might be totally unexpected if its elements were named, although when seen the exquisite propriety of then relation is at once evident.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Emmet_Building

.

No comments:

Post a Comment